[ad_1]

By Natalie Sherman, BBC News

Getty Images

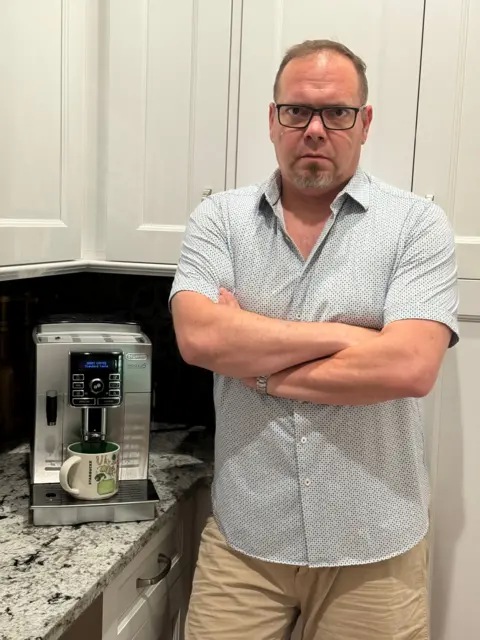

Getty ImagesAndrew Buckley, a self-described “mocha guy”, recently swore off his Starbucks habit, reeling after the firm’s latest price increase sent the cost of his drink above $6.

The 50-year-old, who works in tech sales in Idaho, had been a loyal customer for decades, treasuring his near-daily venti mocha as a little luxury that allowed him to stretch his legs during the work day.

But the company’s latest price increase crossed a line.

“It was the straw that broke the camel’s back on my feelings of inflation in general. It’s like, ‘That’s it. I can’t do it anymore,'” says Mr Buckley, who rang up customer service with complaints before heading to social media to vent.

“I just lost it,” he said. “I don’t plan to be back either.”

The decision was a sign of the bigger troubles brewing at Starbucks, which is hitting new resistance from inflation-weary customers just as fights over unionisation and protests against the company cast as a way to oppose Israel’s war in Gaza are sparking boycott calls and tarnishing the brand.

Andrew Buckley

Andrew BuckleySales at the company slumped 1.8% year-on-year globally at the start of 2024.

In the US – by far the firm’s biggest and most important market – sales at stores open at least a year dropped 3% – the biggest fall in years outside the pandemic and Great Recession.

Among those jumping ship were some of the firm’s most committed customers – rewards members, whose active numbers marked a rare 4% fall compared with the prior quarter.

Former regular David White says he has stopped nearly all of his purchases with Starbucks in recent months, at times abandoning orders mid-purchase, aghast at the totals in his cart.

He says his outrage over price hikes has been bolstered by other company decisions, including its crackdown on workers seeking to unionise.

“They’ve gotten too full of themselves,” the 65-year-old from Wisconsin says. “They’re trying to squeeze their day-to-day customers too much and profit via their employees and prices.”

For Andrew Buckley, the decision to quit the firm was down to prices, but he notes that the various noise surrounding the firm on political issues has left a bad taste in his mouth.

“This is a coffee shop. They serve coffee,” he says. “I don’t want to see them in the news.”

On a conference call to discuss the firm’s latest results, Starbucks chief executive Laxman Narasimhan said sales had been disappointing, citing in part more cautious customers, while acknowledging that “recent misinformation” had weighed on sales, especially in the Middle East.

He defended the brand and vowed to bring back business with new menu items such as boba drinks and an egg sandwich with pesto, speedier service in stores, and a flurry of promotions.

Chief financial officer Rachel Ruggeri said this week that the company was seeing signs of revival, noting growth in active rewards members.

The firm does not intend to back away from its expansion plans, but she warned investors that the challenges would not quickly disappear.

“We do believe it’s going to take some time,” she said.

The firm’s struggles have stirred debate about whether they are a canary-in-the-coal-mine kind of warning that the go-lucky consumer spending that has powered the world’s largest economy in recent years might be abruptly losing steam.

Like Starbucks, a slew of other big fast-food brands, including McDonald’s, Wendy’s and Burger King, have reported softening sales, announcing discount sprees to try to revive enthusiasm.

But many analysts believe Starbucks’ sales drop reveals more about the company than the wider economy.

“When you look back and you see the magnitude of the shift… that occurred in such a short time, that doesn’t usually point to something that’s macro in nature or price point-related in nature,” says Sharon Zackfia, head of consumer at investment management firm William Blair, who raised concern in a note to clients last month that the brand might be losing its lustre.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe company was already under pressure from a years-long fight with union activists, who have raised concerns about pay and working conditions that clashed with the firm’s progressive reputation.

Then in late October, after Starbucks sued the union for a social media post expressing “solidarity” with Palestinians, the dispute landed it in the middle of debates over Israel’s war in Gaza, sparking global boycott calls that took on a life of their own.

Starbucks – not the only American brand to face a backlash over the issue and not a target of the official Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement – has blamed misinformation about its views, after issuing a blanket statement condemning violence in the region.

It has also taken a different tack with the union in recent months – the two sides are now issuing joint press releases claiming progress on contract negotiations.

But the boycott calls crescendoed on social media in January and continue to linger, according to a Bank of America analysis.

Last month, YouTube comedian Danny Gonzalez apologised to his 6.5 million followers for the incidental presence of a Starbucks cup in a recent video after a backlash.

Though Starbucks executives have remained relatively quiet on the topic during sales discussions, as Ms Zackfia puts it: “You’d really be putting your head in the sand not to think that it has had an effect.”

Bank of America analyst Sara Senatore says she had initially been sceptical that the boycott would have a major impact, but other causes seemed insufficient to explain such a sudden and severe sales drop, noting that the firm’s price hikes do not stand out from their competitors’.

She says a quick turnaround could be a tall order, comparing the impact to the brand crisis that faced Chipotle after its stores were found responsible for sparking e-coli outbreaks, which took years to shake off.

“All you can do is try to dampen the sound or essentially overcome it with other things,” she says. “It may just be a matter of time.”

On a recent sunny mid-day in New York, where the density of Starbucks cafes is among the highest in the world, it was hard to gauge the state of the business.

Some shops appeared empty, until customers darting in for a mobile order punctuated the calm.

Even loyal drinkers said they saw opportunities for improvement.

Maria Soare, a 24-year-old in town from Washington, DC, still picks up drinks from the company three or four times a week, but her patronage has dimmed since the pandemic, when it served as a reason to get out of the house.

She says recent price hikes “sting”, and advises the company to “change the food”.

For friends Veronica and Maria Giorgia, the feel of the company has changed.

Veronica, 16, says she doesn’t go as much anymore due to a combination of better options elsewhere, the jump in prices, and recent protests by labour activists.

“That opened my eyes,” she says. “It feels more like a chain.”

And while Maria Giorgia remains a regular customer, the 17-year-old says her perception of the firm has shifted.

“It used to be cool in middle school. Now it’s just convenient.”

[ad_2]

Source link