Local News

Waymo recently mapped the city’s streets, prompting officials and drivers to sound the alarm over self-driving cars.

In cities like San Francisco and Phoenix, autonomous vehicles are a part of everyday life thanks to Waymo. This year, the company deployed manned vehicles to map the streets of Greater Boston, seemingly paving the way for it to bring its fleet of self-driving cars to the area in the near future. But a number of significant roadblocks remain, and a deep skepticism, if not outright hostility, is palpable among many local officials.

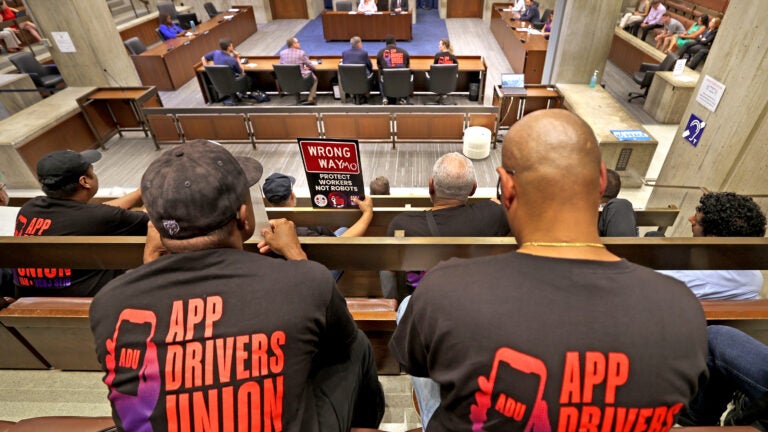

That distrust was on full display Thursday, when the Boston City Council hosted a hearing on the possibility of autonomous vehicles (AVs) operating in the city.

As Waymo representatives touted the company’s safety record and other potential benefits, officials from within the Wu administration stressed that they still had many questions about whether Boston is right for AV deployment. Councilors echoed this hesitancy, while labor leaders and the drivers who could potentially be replaced voiced their deep concerns. After the hearing, a number of councilors joined union members for an anti-AV rally outside City Hall.

Waymo, which is owned by Google’s parent company, Alphabet, says that it has no definite plans for a commercial launch in Boston, and that it wants a robust conversation with local leaders and stakeholders. Legislation is pending on Beacon Hill that would create a regulatory framework for AVs in Massachusetts, and the company could face a steep uphill battle there. Even if some versions of those bills are passed, officials in Boston appear ready to slow-roll the introduction of AVs.

Councilors Henry Santana and Erin Murphy introduced an ordinance Thursday that would create an advisory council to assess how AVs would impact public safety, traffic, local businesses, and much more. The measure would also kickstart a full public study on the potential disruptions AVs would cause, before the company could launch in Boston.

The ordinance, Santana said, is explicitly meant to protect local jobs from “robotaxi takeover.”

“A lot of these drivers are our most vulnerable residents, our immigrant residents, people who are living paycheck to paycheck,” he said.

The Wu administration’s perspective

Chief of Streets Jascha Franklin-Hodge testified during Thursday’s hearing, saying that the deployment of AVs could significantly disrupt life in Boston. The Wu administration, he said, is in favor of taking the process slowly and thinking through every possible effect of AV deployment.

“This is too big, and too important, for us to be reactive,” he said.

Franklin-Hodge did acknowledge that an emerging body of research appears to show that AVs are less likely to be involved in crashes that result in injury. But he stressed that safety is about much more than crash rates.

Do AVs divert other road users into unsafe conditions? Do AVs interfere with first responders? How do they navigate construction zones? These are all questions the administration wants to look into, Franklin-Hodge said.

Congestion is a notable worry. Franklin-Hodge said that he has spoken to officials in San Francisco who estimate that only about 40% of miles traveled by Waymo vehicles in the city were “productive passenger miles,” as opposed to miles where the AV is totally empty. The reason this figure is only an estimate, he added, is because companies like Waymo do not share enough internal data with the cities they partner with. He advocated for strong information-sharing going forward.

Another key factor is the simple reality that Boston’s streets are different from many places where Waymo is currently active. The city lacks a traditional grid system, has many narrow one-way streets, and incorporates heavy pedestrian and cyclist traffic. On top of it all, winter weather can make Boston’s roads even more precarious.

To date, Waymo has not clearly demonstrated that its AVs can handle a city like Boston, Franklin-Hodge said.

“If every Waymo drives like a confused out-of-state tourist, we will very quickly find them unwelcome on the streets of Boston,” he said.

The administration has not taken an official stance on the AV bills in the State House, Franklin-Hodge said, but it does have an interest in helping to shape the regulatory environment of AVs in Massachusetts. There is clearly a market for these vehicles in Boston, he said, but these companies have yet to establish a “strong basis of trust” among the public and the administration would like them to better demonstrate their willingness to be a better partner for local governments.

Waymo’s position

Matthew Walsh, regional head of state and local policy at Waymo, testified Thursday in City Hall. The company is in a “growth phase,” he said. It operates AV services in Atlanta, Austin, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and San Francisco. Waymo is eyeing Washington, D.C., and Miami for expansions in 2026. Manual drivers have been deployed to map more than 10 other cities across the country, including Boston.

Waymo AVs demonstrate an “exceptional safety record,” Walsh said. They are involved in nearly five times fewer injury-causing collisions compared to human drivers. Waymos reduce crashes with serious injuries by 88% and crashes where airbags are deployed by 79%, according to Walsh.

He says that Waymo operates on roads that are similar to Boston’s and does not believe that Boston’s streets are unique enough to prevent safe AV deployment here.

David Margines, director of product management at Waymo, acknowledged that the company has not fully “validated” its AVs for self-driving operations in environments with standing snow on the ground. But they are currently testing in snowy environments in preparation for expansion to places like Boston. Waymo AVs have a diverse array of cameras and sensors on board specifically designed to handle adverse weather conditions, he said.

Responding to concerns about the impact on first responders, Walsh and Margines touted the company’s in-house “ambassador program,” made up of former first responders who help train their counterparts in learning to interact with AVs. Waymo vehicles are designed to recognize emergency sirens from far away and avoid interfering with first responders, they said.

When pressed about the possibility of AVs taking jobs from human drivers, Walsh insisted that this could be offset by the industry adding other types of jobs over the next decade. He also downplayed fears of jobs being taken all at once.

“The idea that Waymo coming to Boston is going to result in people losing their jobs overnight is just not accurate,” he said.

Throughout their testimonies, Walsh and Margines did not appear to curry much favor amongst City Council members. Some of their chosen vernacular, like constant references to “the Waymo driver,” rankled officials.

“Drivers are people. You’re referring to a car as a driver,” Councilor Sharon Durkan said. “I think that is so creepy, and I think that that is so unsettling.”

Organized labor pushback

In testimony during the hearing and during the subsequent rally, union leaders and workers who make a living behind the wheel stressed the need for skilled drivers instead of AVs.

Last year, Massachusetts voters approved a ballot measure allowing rideshare drivers the opportunity to unionize. The new App Drivers Union now boasts a membership of about 70,000 people and is taking a lead in opposing the expansion of Waymo to Boston.

“We’re talking about a direct hit to jobs and our local economy. Drivers who are already stretched thin will be pushed further into debt. They’ll work longer hours for fewer trips, and they’ll be forced to compete with robots. They could lose their jobs to an empty seat,” Autumn Weintraub, executive director of the App Drivers Union, said.

Jack Kenslea, political director at United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1445, spoke about the expertise drivers in that union have that cannot be replaced by AVs. He conceded that many jobs won’t disappear “overnight” but said that “longterm attrition” could slowly erode jobs and weaken protections for workers.

Kenslea pushed back on arguments about AVs being a cost-saving measure for customers.

“What that really means is that the money is taken out of the pockets of the hardworking drivers and community members who are performing these jobs and putting it into the pockets of Google and Waymo executives who are just going to laugh all the way to the bank,” he said.

Steve South, secretary-treasurer of Teamsters Local 25, said that companies like Waymo are simply focused on replacing workers in order to boost profits, recklessly bringing AV technology to more and more places.

“Waymo and other companies that are putting driverless cars and trucks on our roads like to describe themselves as people who are working towards a utopian future. Nothing could be further from the truth. This company is steamrolling into cities throughout our country, without concern for the policymakers, workers, or residents who live there,” he said.

Sign up for the Today newsletter

Get everything you need to know to start your day, delivered right to your inbox every morning.